Participation, permission and momentum

February 15, 2015 § 4 Comments

Don’t wait for permission. If you have an idea that excites you, a thing you want to prototype, a skill you proudly want to share, an annoying bug you want to fix, a conversation you want to convene: don’t wait for someone else to say yes. Just do it!

This is useful (and common) advice for pretty much any endeavor. But, for Mozilla and Mozillians, it’s critical. Especially right now.

We’ve committed to building a more radical approach to participation over the next three years. And, more specifically, we ultimately want to get to a place where we have more Mozilla activities happening than the centralized parts of the org can track, let alone control.

How do we do this? One big step is reinvigorating Mozilla’s overall architecture of participation: the ways we help people connect, collaborate and get shit done. This is both important and urgent. However, as we work on this, there is something even more urgent: keeping up the momentum that comes from simply taking action and building great stuff. We need to maintain momentum and reinvigorate our architecture of participation in tandem in order to succeed. And I worry a little that recent discussions of participation have focused a little too heavily on the architecture part so far.

The good news: Mozillians have a deep history of having a good idea and just running with it. With the best ideas, others start to pitch in time and resources. And momentum builds.

A famous example of this is the Firefox 1.0 New York times ad in 2004. A group of volunteers and supporters had the idea of celebrating the launch of Firefox in a big way. They came up with a concept and started running with it. As a momentum built, Mozilla Foundation staff came in to help. The result was the the first high profile crowd-funded product launch in history — and a people-powered kickoff to Firefox’s dramatic rise in popularity.

This kind of thing still happens all the time today. A modest example from the last few weeks: the Mozilla Bangladesh community’s participation at BASIS. Mozilla volunteers arranged to get a booth and a four hour time slot for free at this huge local tech event, something other companies paid $10,000 to get. They then organized an ambitious program that covered everything from Firefox OS demos to contributing to SuMo to teaching web literacy to getting involved in MDN, QA and web app development — they covered a broad swatch of top priority Mozilla topics and goals. Mozilla staff helped and encouraged remotely. But this really was driven locally and from the ground up.

Separated by 10 years and operating at very different scale, these two examples have a number of things in common: the ideas and activities were independently initiated but still tied back to core Mozilla priorities; initial resources needed to get the idea moving were gathered by the people who would make it happen (i.e. initial donations or free space at a conference); staff from the central Mozilla organization came in later in the process and played a supporting role. In each case, decentralized action led to activities and outcomes that drove things forward on Mozilla’s overall goals of the time (e.g. Firefox adoption, Webmaker growth, SuMo volunteer recruitment).

This same pattern has happened thousands of times over, with bug fixes, documentation, original ideas that make it into core products and, of course, with ads and events. While there are many other ways that people participate, independent and decentralized action where people ‘just do something’ is an important and real part of how Mozilla works.

As we figure out how to move forward with our 2015+ participation plan, I want to highlight this ‘don’t wait for permission’ aspect of Mozilla. Two things seem particularly important to focus on right now:

First: strengthening decentralized leadership at Mozilla. For me, this is critical if we’re serious about radical participation. It’s so core to who we are and how we win. To make progress here, we need to admit that we’re not as good at decentralized leadership today as we want or need to be. And then we need to have an an honest discussion about the goals that Mozilla has in the current era and how to build up decentralized leadership in a way helps move those goals forward. This is a key piece of ‘reinvigorating Mozilla’s architecture of participation’.

A second, and more urgent, topic: maintaining momentum across the Mozilla community. It’s critical that Mozillians continue act on their ideas and take initiative even as we work through these broader questions of participation. I’ve had a couple of conversations recently that went something like ‘it feels like we need to wait on a ‘final plan’ re: participation before going ahead with an idea we have’. I’m not sure if I was reading those conversations right or if this is a widespread feeling. If it is, we’re in deep trouble. We won’t get to more radical participation simply by bringing in new ideas from other orgs and redesigning how we work. In fact, the more important ingredient is people taking action at the grassroots — running with an idea, prototyping something, sharing a skill, fixing an annoying bug, convening a conversation. It’s this sort of action that fuels momentum both in our community and with our products.

For me, focusing on both of these themes simultaneously — keeping momentum and reinvigorating our architecture of participation — is critical. If we focus only on momentum, we may get incrementally better at participation, but we won’t have the breakthroughs we need. If we just focus on new approaches and architectures for participation, we risk stalling or losing the faith or getting distracted. However, if we can do both at once, we have the chance to unlock something really powerful over the next three years — a new era of radical participation at Mozilla.

The draft participation plan we’ve developed for the next three years is designed with this in mind. It includes a new Community Development Team to help us keep momentum, with a particular focus on supporting Mozilla community members around the world who are taking action right now. And we are setting up a Participation Task Force (we need a better name for this!) to get new ideas and systems in place that help us improve the overall architecture of participation at Mozilla. These efforts are just a few weeks old. As they build steam and people get involved, I believe they have the potential to take us where we want to go.

Of course, the teams behind our participation plan are a just a small part of the story: they are a support for staff and volunteers across Mozilla who want to get better at participation. The actual fuel of participation will come from all of us running with our ideas and taking action. This is the core point of my post: moving towards a more radical approach to participation is something each of us must play a role in. Playing that role doesn’t flow from plans or instructions from our participation support teams. It flows from rolling up our sleeves to passionately pursue good ideas with the people around us. That’s something all of us need to do right now if we believe that radical participation is an important part of Mozilla’s future.

We are all citizens of the web

November 10, 2014 § 1 Comment

Ten years ago today, we declared independence. We declared that we have the independence: to choose the tools we use to browse and build the web; to create, talk, play, trade in the way we want and where we want; and to invent new tools, new ways to create and share, new ways of living online, even in the face of monopolies and governments who insist the internet should work their way, not ours. When we launched Firefox on on November 9, 2004, we declared independence as citizens of the web.

The launch of Firefox was not just the release of a browser: it was the beginning of a global campaign for choice and independence on the web. Over 10 million people had already joined this campaign by the time of the launch — and 10s of millions more would join in coming months. They would join by installing Firefox on their own computers. And then move on to help their friends, their families and their coworkers do the same. People joined us because Firefox was a better browser, without question. But many also wanted to make a statement with their actions: a single company should not control the web.

By taking this action, we — the millions of us who spread the software and ideas behind Firefox — helped change the world. Remember back to 2004: Microsoft had become an empire and a monopoly that controlled everything from the operating system to the web browser; the technology behind the web was getting stale; we were assaulted by pop up ads and virus threats constantly. The web was in bad shape. And, people had no choices. No way to make things better. Together, we fixed that. We used independence and choice to bring the web back to life.

And alive the web is. For all 2.8 billion of us on the web today, it has become an integral part of the way we live, learn and love. And, for those who think about the technology, we’ve seen the web remain open and distributed — a place where anyone can play — while at the same time becoming a first class platform for almost any kind of application. Millions of businesses and trillions of dollars in new wealth have grown on the web as a result. If we hadn’t stood up for independence and choice back in 2004, one wonders how much of the web we love today we would have?

And, while the web has made our lives better for the most part, it both faces and offers new threats. We now see the growth of new empires — a handful of companies who control how we search, how we message each other, where we store our data. We see a tiny oligopoly in smartphones and app stores that put a choke hold on who can distribute apps and content — a far cry from the open distribution model of the web. We see increased surveillance of our lives both by advertisers and governments. And, even as billions more people come online, we see a shift back towards products that treat people as consumers of the digital world rather than as makers and as citizens. We are at risk of losing our hard won independence.

This is why — on the 10th birthday of Firefox — I feel confident in saying that Mozilla is needed more than ever. We need great products that give people choices. We need places for those of us who care about independence to gather. And we need to guard the open nature of the web for the long haul. This is why Mozilla exists.

Just as we did 10 years ago, we can start to shift the tide of the web by each and every one of us taking concrete actions — big or small. Download the Firefox 10th Anniversary release — and then tell a friend why Mozilla and Firefox still matter. Grab a colleague or a parent or a kid and teach them something about how the web gives them independence and choice. Or, just watch and share the Firefox 10 video with friends (it’s really good, honest :)). These are a few small but meaningful things you can do today to celebrate Firefox turning 10.

Putting the web back on course as a force for openness and freedom will require much more than just small actions, of course. But it’s important to remember that the global community of people who installed Firefox for others — and then talked about why — made a huge difference when Mozilla first stood up for the web. We moved mountains over the past 10 years through millions of people taking small actions that eventually added up to a groundswell. As we look today for new ways to shore up our independence on the web, we will need to do this again.

Th 10th Anniversary of Firefox is a day to celebrate, no doubt. But today is also a day to deepen our commitment to choice and independence — to stand together and start sharing that commitment with everyone around us.It is a day to show that we are citizens of the web. I hope you will join me.

Mozilla and the web makers

September 7, 2011 § 6 Comments

When I say ‘maker’, most people understand what I mean: a DIY ethic, a hankering to create. Often, makers are into robots and gadgets. Physical things. But the web is also filled with people who love to tinker, create and make.

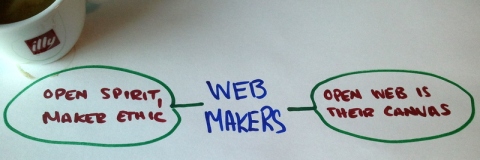

In my last post, I argued that Mozilla should engage these ‘web makers’ as we refine and evolve what we started with Drumbeat. Which begs the question: who are the web makers?

Looking at the people who have joined our community recently, I see teachers, filmmakers, journalists, artists, game makers and curious kids who a) want to be part of what Mozilla is doing and b) are making things using the open building blocks that are the web. I believe Mozilla has alot to offer these people, and vice versa.

To understand this, it’s worth looking at the people who have gotten involved Mozilla as a result of Drumbeat. Here are three examples:

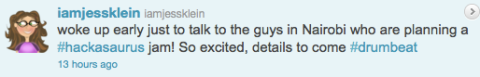

Jess Klein is a designer who teaches kids about technology. She’s designed games. She’s worked for Sesame Street. And now she’s helping Mozilla bring Hackasaurus to life, designing a whole new way for kids to learn about the web.

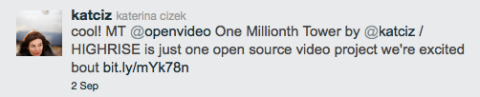

Kat Cizek is a documentary filmmaker. She’s chronicled the participatory media org Witness. She’s won an Emmy for a web documentary she made in Flash. And now she is making a whole film with Popcorn and WebGL, a film made for the browser and solely with the open building blocks that make up the web.

Cathy Davidson is an iconoclastic professor at Duke University. She let’s her students choose their own grades. She wrote a book about how the web is rewiring our institutions. She also built out a huge part of last year’s Mozilla Festival, and now is helping us figure out where to go next in education.

These people have some things in common. They share Mozilla’s open spirit and maker ethic. They see the open web as a canvas for their ideas. They are building things with the web. And they are all actively contributing to Mozilla.

I like to think Mozilla offers these people something special: a chance to build — and learn– alongside people from Mozilla’s more traditional community who are creating the cutting edge of the web. This is what we’ve started with Drumbeat.

On the flip side, these people clearly have something to offer Mozilla: help building a world where millions more people understand that the web is about making things.

This is why I want these people actively involved in shaping where Mozilla goes in the future. In my next few posts, I will talk about how these people can help us build on the work we’ve started with Drumbeat, especially how we teach and build tools for web makers.

A question in the meantime: what do others think about the role the people I am describing here can play in Mozilla?

NextBeat: a generation of web makers

August 31, 2011 § 7 Comments

We started Drumbeat as an experiment to bring new people and new ideas into Mozilla. Some results from the first 18 months: 20,000 people signed up, dozens of new community leaders and solid core projects like Hackasaurus, School of Webcraft, Popcorn, MoJo and OpenBadges.

While I’m proud of all this, I actually think Drumbeat’s biggest achievement has been carving out a new way for Mozilla to work: teaching and building things with people I call ‘web makers’.

The projects at the core of Drumbeat have been built by matching teachers, filmmakers, journalists, artists, game makers and curious kids with the kind of developers who make up Mozilla’s more traditional community.

While these new community members come from different backgrounds, they have two things in common: 1) they share Mozilla’s open spirit and maker ethic, and 2) they want to use the open web as a canvas for their ideas.

As part of Mitchell’s broader conversation about the next era of Mozilla, I want to explore how we can work with these web makers to refine and evolve what we’ve started with Drumbeat.

Specifically, I want to explore how we weave teaching and building things with web makers into the core of Mozilla’s work. The MoFo team came up with some early thinking on this over the summer:

- We set up Drumbeat to figure out how to extend our mission beyond Firefox (and beyond software).

- What we found: Mozilla has an opportunity to build the next generation of web makers. This opportunity is huge.

- This is partly about teaching: helping people learn how to use the building blocks that make up the web.

- It’s also about making tools: tools for creativity, tinkering and invention. Built by and for web makers.

- We can — and should — do these things. They will keep the Mozilla spirit alive, advance our mission, and build our values into the future of the web.

Of course, Mozilla should continue to invent and evolve the core building blocks that make up the web. That is what we’ve always been good at.

But — as our early work in Drumbeat has shown — teaching people how to use and extend these building blocks also has huge potential to advance Mozilla’s cause. As Mitchell said last year in Barcelona:

One of the values of Mozilla is that we *build* things. Moving individuals from consumption to creation is Mozilla’s goal.

Reaching this goal will take millions of individuals teaching each other how to build things, and then extending how things are built. I can imagine Mozilla as a new kind of learning institution and open research lab that brings these people together. That’s something that can — and should — be a part of who we are.

In my next posts, I plan to explore this web maker concept and introduce some of the new people who have joined Mozilla through Drumbeat. I will also float some concrete ideas on how we can refine Drumbeat with the help of these people, rolling it back into the mainstream of Mozilla and growing it into something bigger at the same time.

Media, freedom + the web: berlin talk

March 24, 2011 § 5 Comments

As I pointed out a while back, this year is Marshall McLuhan’s 100th birthday. It’s a good time to be thinking about media and the web: in particular about how the free and open medium of the web is shaping all media that came before. Increasingly, this is a theme for Mozilla Drumbeat in 2011.

Why now? Yes, partly because it’s Marshall’s birthday. But more importantly, we’re at a key juncture: traditional media are increasingly reinventing themselves by tapping into the essence of the web; at the same time monopolies in spaces like social networking and mobile apps are calling the freedom of the web into question. Things could go either way: open or closed.

Back in February, I explored this theme in the annual Marshall McLuhan Lecture at the Canadian Embassy in Berlin. I’ve re-recorded the talk and posted it here:

It’s a long talk: 40 minutes. If you just want to get a feel, you can flip through the PDF version. Or, you can download an mp3 audio version or an ogg video version.

At a high level, I believe we have to make a number of critical choices in coming years that will impact media and society for decades to come. My three top level points are:

We rarely call it out, but the same basic principles that make free software and open source great are also baked into the very fabric of the web itself. The web gives us the freedom to use, study, remix and share — that’s what we are all doing at a massive scale. We do these things because they are baked into both the technical building blocks and the culture of the web. When we think about the web as the medium that is shaping our times, it’s important to remember that this kind of freedom that is central to what’s going on.

McLuhan said: “The next medium, whatever it is – it may be the extension of consciousness – will include television as its content, not as its environment, and will transform television into an art form.”

This has happened. And it hasn’t just happened to television. All media have become the content of the web. As a result, all media are wrapped in this context of freedom: in a world that lets you bend and share without asking permission. The initial reaction from old media was push back. But times are changing. We’re very clearly entering a phase where smart media players are using the essence of the web to reinvent themselves. Eg. witness the Guardian and Wikileaks or Al Jazeera in Egypt.

The context is a web built on freedom. The opportunity is that all media are reinventing themselves in this context. If we seize this opportunity, we can bake things like transparency, remix and sharing into the media culture and practice for the next 100 years. That’s what we’re trying to do with Mozilla Drumbeat projects like popcorn.js: build tools that give filmmakers and journalists access to the essence of the web. If we succeed, we also bake the web into how whole industries work and think.

Of course, there is another direction we can choose: we could close down the web. Tim Wu talks eloquently about this in his book the Master Switch. Talking about media empires in the last 100 years, he says: “Open eras tend to last for about 15 – 20 years. And then they flip into being more closed. We may be at the beginning of the closing with the internet.”

Specifically: we could give up our privacy and identity to one or two social networks; we let one or two companies decide who gets to innovate and create software; we could let governments decide whether we get to access the internet at all. The result would be a very different web than the one we have now.

It’s this point about choice that makes media such an important theme for Mozilla and Drumbeat in 2011: now is the time to aggressively, creatively and playfully promote web technology and web thinking in the broader world of media. What we do now will shape media — and society — for a long time to come.

I’d love to get people’s feedback on the ideas in this talk. And, even more, I’d love to see people building things and playing with the theme of media, freedom and the web as part of Mozilla Drumbeat in 2011.

This is the third in a series of posts about media, freedom and the web. I’m hoping to do more, including a few posts on the future of cinema.

Drumbeat: what’s next?

September 2, 2010 § 18 Comments

We’re eight months into Drumbeat. We’ve built a bit of a brand. People are interested. They want to get involved. More importantly: new people have shown up. Educators. Filmmakers. Artists. Not Mozilla natives. These new people are doing interesting things. And their peers are noticing.

It’s is a good start. We have some momentum. There is potential. Which begs the question: now what?

One thing is clear: we need to turn interest into action and impact. With 2011 on the horizon, I’m asking: how do we best do this? What does Drumbeat do next?

I want to know what you think about this. As comment fodder, here are three + one things I think we should focus on as Drumbeat moves into 2011:

0. Narrow our focus. Pick grokkable, magnetic topics.

Drumbeat started with a very broad call to action: ‘help keep the open web open‘. This didn’t work as well as we’d hoped. Some people responded. Most just stared back blankly.

Recently (and somewhat by accident), we’ve shifted focus to more specific mashups of Mozilla’s mission and other people’s big ideas. Re-invent cinema using the open web. Use the culture of the web to transform education and learning. And so on.

These mash ups have been much more magnetic. People already excited about the big ideas in question have looked up and said: ah, the web people are interested. Cool. How can I join in?

No matter what else we decide to do, one of our next steps should be to consistently use these ‘somebody’s big idea + open web tech and culture’ combos to focus what we’re doing. On the flip side, we should (dramatically) turn down the volume of the generic ‘help the open web’ angle.

1. Follow through on what we’ve started. Amp up participation and impact.

During the last eight months, we’ve dug our teeth into some awesome and substantial projects — Web Made Movies, Mozilla / P2PU School of Web Craft, Universal Subtitles. And it’s possible we’ll start work on a couple more by year end.

Each of these projects has big dreams. They also have clear goals for the coming year. A web developer education program that is 10,000 learners strong. A bustling open video studio pumping out productions with leading directors from around the world. Grassroots subtitling taking hold on well known, globally important video sites. These are amongst the 2011 goals Drumbeat projects shared in Whistler.

One answer to ‘what’s next for Drumbeat?’ is ‘follow through and help these projects reach these goals’.

There are three primary ways we can do this. Help with the technology side of these projects (e.g. P2PU leveraging Labs’ open social tools). Build fundraising capacity by actually designing and running campaigns with the projects (we’re doing major campaigns this fall and into next year). And, bring more people and profile to the table (e.g. volunteer recruitment in mainstream Mozilla newsletters and more promotion on Mozilla sites).

Helping in these ways will drive participation and impact in the projects we’ve already started. This, for me, is the baseline of what Drumbeat should do next. If that’s all we did in 2011, would it be enough? Personally, I don’t think so.

2. Get get good at open innovation. Find and grow more promising ideas.

We’ve always seen Drumbeat as a way to get many good ideas on the table, and then to back the best. A decent number of people have responded to this aspect of what we’re doing — there are now over 220 projects on drumbeat.org.

We’ve highlighted and helped a handful of these projects in small ways. Promoting them in our newsletter. Setting up peer coaching on our community calls. But, overall, we haven’t yet figured out a good and sustainable way to help these projects evolve, expand and succeed.

What we need is a simple, systematic way to find and grow promising ideas. One approach: combine the Mozilla labs open innovation process with the ‘magnetic topic mashups’ described above. Pick a topic. Run an innovation challenge. Back the best ideas that come out of the challenge.

For example, we might run a challenge around the question: how can the culture and technology drive innovation in the world of journalism? The challenge process would get many ideas on the table, spark collaborations. We’d offer fellowships or grants to the ‘winners’ of the challenge.

If Jetpack for Learning was any indication, this approach is more likely to yield results than the general Drumbeat ‘propose a project that helps the web’ call to action we’ve been using so far. One of our priorities for 2011 should be to put this open innovation model centre stage, pick some awesome topics and see what we learn.

3. Spark people’s imagination. Make it easy for them to connect. Focus on (big) visibility.

While our existing projects are awesome and important, Drumbeat (and Mozilla as a whole) needs another side to it — a side that is lightweight, easy to engage and, well, sexy.

Why? Because part of our goal with Drumbeat is to spark people’s imaginations — to get millions of people excited about how the open web can liberate, empower and delight them.

If you look at this from a ‘what’s next?’ perspective, this is partly a matter of linking what we’re doing already to things people care about. Making Web Made Movies with well loved producers and artists. Connecting Universal Subtitles to widely known content brands. Showcasing robots, lasers and other shiny open tech toys at Drumbeat events. The good news: we’re working on all these things.

However, ‘sparking imaginations’ need not — and probably cannot — be completely tied up in the idea of Drumbeat projects and events. We should embrace anything we can dream up that delights and engages, and the connects people to Mozilla outside of their day to day experience of using our products.

Google showed how you can do this with it’s recent HTML5 Arcade Fire video. It was a lightweight, fun, internet-scale way to demo what HTML5 video can be. And people loved it.

We hope to do something similar with our upcoming Firefox 4 parks campaign with the World Wildlife Fund — using sexy demos to make the link between the forests of the amazon and the web ecosystem that Firefox helps sustain. We’ve got other ideas up our sleeves as well (including some involving cats!)

But, the fact of the matter is, Mozilla isn’t naturally good at this. We’re more often than not too earnest about the web. We need to develop or lighter sexier side. Especially if we want millions of people across the web to join and support our cause. In terms of Drumbeat next steps, this is a major area we need to work on.

—

These are early thoughts that need much shaping and refinement. I’m interested to know: Which sound right? Which sound exciting? Which sound unachievable? You’ve been watching Drumbeat unfold. Where do you think it should go next?

I’ve posted an etherpad version of this content for people to hack on. And you can also make comments below. I’ll feed whatever people post into a Mozilla board discussion mid-September. And, if there is alot of interesting changes, I’ll repost the full etherpad version here.

PS. I know this post is too long. Sorry about that. I really want to see how people react to the whole set of ideas here — so my attempts at chopping it into a bunch of smaller posts didn’t work.

10 days of freedom in Barcelona

August 27, 2010 § 3 Comments

I just had a fun breakfast with Simona Levi from ExGAE/ / oXcars. What I learned: Learning, Freedom and the Web isn’t the only interesting thing happening in Barcelona two months from now. There are at least seven open internet / open education / free culture events happening over the span of 10 days.

Between October 28 and November 6, Barcelona will host: the 2000 person oXcars free culture festival; the Free Culture Forum; the P2PU summit; Open Education 2010; Drumbeat Learning, Freedom and the Web; an open ed play day in the Raval; and possibly a Communia meeting. Phew.

We should find a way to shout and promote all of this. Barcelona will be the global epicentre of free culture / open education / open web stuff for 10 days this fall! We need a phrase or a name for it. ‘10 days of freedom‘? ‘Barcelona abierto‘? Not sure, but Simona and I agreed to call out for suggestions. If you have ideas, post them below.

PS. goes w/o saying -> book an extended trip to Barcelona if you can.

Experiment: badges, identity and you

August 12, 2010 § 10 Comments

Figuring out who to pay attention to and who to work with is a big challenge in a community like Mozilla. Using the Whistler Science Fair as example, Les Orchard points out the underlying issue — we don’t have a quick way to parse through all the awesome to find out who’s good at what / who’s contributed what / who is doing things relevant to me. This is a common problem in online life overall. We don’t have an easy, portable and reliable way to represent our skills, achievements and social capital.

Over the last two months, I’ve been talking to people about this same challenge in another context — learning and education. Historically, we’ve used degrees and certificates to show what we know. This breaks down online — partly because we have no good way to show these credentials and partly because so much of our learning is now informal that degrees aren’t really relevant. People like P2PU, Remix Learning and others have come same conclusion Les has — we could use online badges to represent these things. Sites like Stack Overflow already use badges like this. We’re going to do the same for the Mozilla / P2PU School of Webcraft.

Which brings me to the experiment I want to do: a digital ‘backpack’ that lets you store and display badges you pick up from many different sites across the web.

Badges can provide a good way for potential friends, collaborators, co-workers and employers to size you up. However, that’s only true if they can associate all your badges with you. You don’t want to send them traipsing around the web to look at sites like P2PU, iRemix and Badger to see your badges. Instead, you want to all the badges from these different places reliably associated with your online identity.

With this in mind, I’ve been talking to Mike Hanson and others about an experiment that displays badges from multiple places as a part of the identity you build up through Firefox. Someone wanting to check you out would see something like this:

At an implementation level, this would work by storing your badges (or references to your badges) in both a personal data vault like Weave and some sort of claims system. It could work something like this:

The main ‘layers’ of this system are the 1. the badge issuer, 2. you and your online identity and 3. badge display and badge viewers. Specific to my proposed experiment are:

- P2PU, Badger and iRemix -> these are places where you *get* a badge for some skill or activity. They act as ‘badge servers’ and would expose all the badges they have awarded to you in a structured and standardized way.

- A personal data vault (e.g. Weave) and a claims system (Mike Hanson is working on a general system like this) -> from a user perspective, these items combine into a ‘personal badge manager’ that you access via identity tools in your browser or on a web site.

- Your identity profile (webfinger?) plus social media sites like LinkedIn -> these display all of your badges and associate them with the rest of your identity.

At a practical level, we need a system like for P2PU School of Webcraft and the kind of badge platform Les is proposing for Mozilla. Connecting badges a version of your online identity the you control also presents a huge opportunity in informal digital learning — everyone working in that space needs something like this as well.

With this in mind, my proposal is to roll out an proof of concept for the idea described above using badges from Mozilla, P2PU and various orgs in the MacArthur Digital Media and Learning Network. I’m going to work with Mike, Les, Philipp, Robert and others on this in the next few months, with the hope of showing the prototype at the Drumbeat Learning, Freedom and the Web Festival in Barcelona this November. If you’ve got ideas or want to help out, please post comments below.

What challenges do hybrid orgs face?

May 20, 2009 § 6 Comments

It’s probably clear by now that I’m a keener for orgs mashup public benefit mission + market disruption + the participatory nature of the web. Mozilla is one such organization and, as I look around, I see others. There is alot of up side to how these orgs work, especially the potential to move markets towards the public good at a global scale. But there are also a ton of very real challenges in making these orgs work. That’s what I want to write about today.

From where I sit, the biggest challenge is explaining ourselves. The hybrids that I am talking about tend to have both missions and org models that people haven’t seen before. As shaver said to me in a tweet, this means we ‘…have to use 500 words to explain what we do, vs. five words for a pure for-profit or non-profit play.’ Fixing this is no small task, and it quickly cascades out into other problems.

Think about this in the Mozilla context for a moment. First off, we need to explain that we exist to promote and protect the open nature of the internet. While this mission fits well within the centuries old tradition of public benefit organizations, it’s not easy to point to similar examples that help people immediately understand what kind of beast we are. Red Cross? Sierra Club? Public radio? There are overlaps with all of these, but none provide a perfect parallel. The result: a whole bunch of long winded explaining.

Even if the mission comes across, there is still the organizational model to communicate. This matters less at first blush. Who but the taxman really cares whether an org looks like a company, a charity or a little bit of both? It turns out that many people do. As I travel around talking to people about Mozilla, I am finding that everyone loves Firefox (no surprise) but almost noone knows it’s made by a global community of volunteer contributors backed by a public benefit org (this has surprised me). When I explain a bit, I get happy surprises. Things like “wow, that makes Firefox even cooler’ and ‘I didn’t know I could get involved’. Once people get Mozilla’s model, it excites them. However, the lack of a shorthand way of explaining all that is bundled up in ‘hybrid org’ means it takes a bunch of explaining to get to that point of excitement.

This challenge of explaining ourselves is what lilly might call a ‘big poetry problem‘. Getting the poetry right is an essential element of success. However, hybrid orgs also face a ton of significant challenges on the pragmatic front. Decision making. Structure. Engagement. Investment. Staff recruiting. Management. Participation. Product. Public relations. Organizing resources. Revenue. Leadership. It’s not that other orgs don’t face challenges in these areas. However, the nature of these problems is often quite different when you’re working with a hybrid model.

Take the intersection between ‘participation’ and ‘product’ as one example. Many non-profits are focused on public participation. These orgs use well honed engagement and facilitation techniques to get people out, harnessing community effort to raise important issues, clean up parks and so on. However, until recently, this kind of mass participation was rarely used to make specific, high quality products (or services) that need to ship at a specific time and succeed in the market. Until recently, creating products and services that will be used by large numbers of people has been the domain of big companies and governments who can marshal trained specialists and set up big management structures.

Organizations like Mozilla turn this upside down and sideways. They combine the mass participation of social movements with the ability to create high quality, desirable (public) goods that people will use every day. This is where the challenge comes in: we don’t have well established models managing, facilitating and leading in this kind of environment. Hybrid orgs are inventing these models, finding ways to create good goals and scaffolding, focus on participation, let people scratch their own itch. The thing is, there is no clear roadmap on how to do this and the daily pragmatics are hard. There is a need for constant reflection, tweaking and a kind of personal + collective honesty that’s hard to come by.

‘Structure‘ is another good issue to look at from a hybrid org perspective. We have well established legal structures for create non-profit, public benefit organizations. Yet, in every country that I know about, these structures work poorly when people try to hybridize and innovate what it means to do public benefit work. They have trouble keeping up with new and emerging public benefit roles in society (example -> Wikipedia providing universal access to all human knowledge). They aren’t well tuned for organizations that participate in the market with a public purpose (example -> Firefox pushing open standards back into the mainstream of web development). And they don’t account for the critical role that volunteer contributors play as a form of public support and participation (example -> Mozilla localizations). The frameworks we’ve developed for charities over the last few hundred years just haven’t caught up to these new ideas yet.

The result is that many hybrid organizations must engage in pretzel like contortions in order to find a structure that works. In Mozilla’s case, we’ve set up a charitable foundation as well as a number of wholly owned commercial subsidiaries. All of these organizations share the same mission of promoting the open nature of the internet. All of them engage with community members to create products and services that advance this mission. And all all of them can demonstrate huge public support and participation. Yet, we run them as separate organizations. In some ways, this isn’t the end of the world, and it certainly seems like the safest option given the ambiguities of charity law. But there is no question this pretzel like structure adds strategic and operational overhead, and can just plain confuse people. There are definitely days where I wish we could just be one public benefit organization called ‘Mozilla’.

Of course, ‘participation’ and ‘structure’ are only two examples of pragmatic challenges that hybrids face. You could also dig into the question of investment, and in particular the fact the hybrids are percieved as a bad fit for both private investors and traditional grantmakers. This makes it tough to scale, compete and move the market. Or you could explore the revenue side. Hybrids must constantly ask: what kinds of income are going to align with — or at least not disrupt — our public benefit mission? Leadership — and how you balance it with distributed decision making and the culture of the web — also seems pretty central. The list of questions and challenges is pretty long.

My goal here is not to go deep on every major challenge, but to set the tone and get others talking. What do you see as the biggest challenges that hybrid orgs face? And do you know of hybrid orgs that have overcome these challenges? I’d love to see responses to these questions as comments and trackbacks. Also, we’re planning to talk about these questions with a few organizations that feel similar to Mozilla at a small gathering next month. My hope is that simply mapping the challenges and looking at how people have tackled them will go a long way towards helping us make our hybrid organizations better. Once we’ve done a bit more of this, I promise to loop back and synthesize what people are saying. Should be interesting.

Why do hybrid orgs matter?

May 12, 2009 § 10 Comments

I’ve been poking at the question ‘why do hybrid orgs matter?’ for a couple of days now. Emailing friends and colleagues. Grilling people over dinner. Drawing little doodles. As I did this, I kept stumbling around ideas like ‘huge impact’ and ‘creating public goods’ and ‘massive participation’. Important ideas, but not quite what I was hoping for. It turns out that coming up with a crisp, helpful ‘why hybrids matter’ statement is tough.

It’s tough because the ideas we’re playing with here are (in part) very new, and the term ‘hybrid organization’ is still quite fuzzy (there are many different takes on hybrids beyond what I am talking about). However, the more I dig, the more I am convinced that organizations like Mozilla, Wikipedia, Kiva, Miro and so on that mashup mission, market and the culture of the web represent a new pattern worth understanding. Even if we don’t yet have the right words to describe this pattern yet, we need to dive in, think and play.

So, that’s what I did. I rolled up all the notes and email comments I gathered in the last few days into a short ‘why do hybrid orgs matter?’ blurb that goes like this:

Mission + market + web hybrids matter because they can wield the power needed to move markets at a global scale, while still looking out for the small guy, taking the long view and staying true to their public benefit mission. They show us how organizations could — and maybe should — work in the future.

It’s pretty awkward and wordy, and in a number of ways not quite right. That’s okay. Even more than earlier, my hope here is to spark conversation. Why do mission + market + web hybrids matter to you? What would you add to this statement?

As a way to feed the conversation, I figured it would be useful to share some quotes from the email conversations I’ve been having and notes on my own thinking. They break down into six things that matter about hybrid orgs:

1. Power to move markets …

This one comes from something johnolilly said in email: “Sometimes we need organizations with financial and market strength but mission-orientations to keep capital-only-organizations doing the right things for the commons. Historically, those with money, and money-missions, have had all the power. Hybrids are important because they have the potential to let mission-oriented orgs wield similar power, but for human-oriented needs.” No question this is at the core of what matters.

2. … at a global scale …

tonyasurman agreed but pushed one step further: “What’s unique about hybrids is the ability to take move market but also the ability to do this at a global scale without losing the integrity of the small. This is really important. Non-profits and social enterprises have never had the potential for this kind of impact. Hybrids can take public benefit products and services to a scale never before imagined.” The global scale that comes w/ the web also seems critical, and not just on the market transformation side. It’s an essential part of creating high quality products and services using peer production.

3. … while still looking out for the small guy …

Global scale, high quality product and public benefit mission mean that hybrids tend to be good at getting great stuff into the hands of incredibly tiny, otherwise-ignored markets. nreville said: “These hybrids are able to bring the full benefits of market influence to underserved constituencies that would otherwise be completely ignored a big company or poorly served by traditional charity. If someone made a special browser for just for people who speak Telugu it would probably suck. But Mozilla is willing to put energy into translating Firefox into Telegu, even when it’s not profitable to do so. The result is that a small constituency gets a world-class product.”

4. … taking the long view …

Similarly, hybrids can think beyond short term gain and consumer support. beltzner wrote: “Hybrid organizations have a distinct advantage over traditional organizations in acting for long-term benefits. Many traditional organizations, concerned with quarterly performance and growth, are consumed with what they can do to increase their immediate position at all costs. Hybrid organizations, concerned with public benefit and ecosystem growth, can trade off immediate short-term advantage with long term development more easily. For example, while a traditional organization may find it difficult to stop activities which have a short term benefit but a long term detriment, a hybrid organization approaches that decision differently. Practically speaking, this also means that hybrid organizations are as concerned with *how* they do things or develop systems as they are concerned with the things themselves.”

5. …. and staying true to their public benefit mission.

Responding to my first post, stephendeberry asked: “how do you ensure the public benefit remains core to the hybrid model?” This is actually a huge challenge for both traditional non-profits (grantmaker demands trigger mission drift) and social enterprises (can become more about the market than the mission). And it’s somewhere I think hybrids built on the idea of mass participation and peer production have a special advantage. They not only have boards and leaders committed to the mission, but they also have huge communities actively involved in interpreting the mission every day by helping to make something. The aggregate decisions of people who contribute to Firefox, or Wikipedia, or Kiva help shape what these things are in very real ways, which is in turn likely to make sure things stay more or less on mission. This isn’t to say peer production is democracy. Usually, meritocracy is the rule. Still, having a massive number of stakeholders involved in building things helps hybrid orgs stay public benefit focused.

6. Hybrids can show us how organizations could — and maybe should — work.

The organizational tools available to us as a society are quite broken, or at least don’t fit all the things we need and want to do. The current economic crisis shows this. The overly bureaucratized world of grant dependent non-profits shows us this. And, on a more positive side, the growth of massive informal social movements shows this. We don’t have good organizational models (or legal incorporation structures) to figure out how to channel the energy of huge numbers of people who want to play across mission and market make things better in a coherent, collaborative, high-impact and sustainable way. The hybrids I am talking about are taking a shot at fixing this, inventing and evolving new ways to organize as they go. This is pretty meta, I know. But it’s also pretty important.

7. ….?

I think there is some good stuff in here. But it definitely isn’t completely right yet. So, the question now is: what’s the seventh item on this list? The eighth? And the ninth? I really want people to add to this list, to poke at it further and to call out the bits that feel like just plain bull. The more I struggle with these ideas, the more I think conversation is useful.

Why? Because figuring out why these organizations matter, what makes them tick and what challenges they face (my next post) is a part of making them work better. Working in uncharted waters is hard. Sharing what we’re learning along the way helps. It helps those of us trying to nurture organizations and communities that mix mission, market and the web. And it provides fuel and encouragement to people who want to set up such organizations anew.

You must be logged in to post a comment.